Most developers are familiar with the Open-closed Principle in object-oriented programming. Entities should be open for extension but closed for modification. It serves as a useful guide for software design.

In object-oriented programming, the open/closed principle states “software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification”; that is, such an entity can allow its behavior to be extended without modifying its source code.

The philosophy of the open-closed approach is also useful outside of OO development. Last year I joined a new development team that uses Jenkins, an open source automation server, to run its continuous builds. It’s a small team and each developer is expected to maintain their own builds. Previously, I’d never had to manage Jenkins or any other continuous build system, so it’s been a learning process for me.

Fortunately, I’d worked with devops guru Carolyn Van Slyck with a previous employer. Following her example, I learned how to set up a robust build system where she essentially applied the open-closed principle to her build architecture.

Why Is This Important?

Before diving into the details, let’s discuss the importance of this type of architecture. The motivation behind this approach was a project where all build steps were saved in the CI automation system. In this case it was Bamboo.

At first Bamboo was locked down so only a select few administrators had access. This was a new project so application developers were constantly requesting changes to the build steps. To move things along, developers were given full access to update the Bamboo jobs as needed. This led to chaos. They made daily tweaks with no way to track changes. Failing builds were difficult to diagnose and fix.

A Better Way

For the next project, Carolyn implemented a better solution. She introduced NANT scripts as extension points, and these scripts were committed to the source code repository along with the application code. Each script represented a well known point in the build that developers could tap into. You could have prebuild.build to handle NuGet or NPM dependencies, test.build to run tests, deploy.build to deploy to a hosting environment, etc.

There was also a bin directory for utilities needed specifically for the build thus alleviating one off installation requests for Bamboo administrators. For example, ctt.exe, a .NET configuration transformation tool, could be committed to bin and be made available for the build without having to install it on the build server.

The success of this approach made an impression. I took these same ideas and implemented them in my current position. The benefits are twofold.

One, developers no longer need access to the build system to update build steps. Administration of the build infrastructure is locked down to a few system admins who focus mostly on scalability and security and not on the details of a specific application. Build jobs all look the same because they’re calling into the same set of scripts every time. In fact, creating a new job is as simple as cloning a template and pointing it to a code repository.

Two, application developers can tweak a build simply by editing a script, testing the change locally, and committing it to the source control system. Changes to the script files are automatically tracked via its version control history. This is a huge help when tracking down issues.

Currently, I’ve implemented this approach using Jenkins for the CI system and NANT to handle the steps, but it could apply to any tool. In fact, I’m currently working on a web app where npm run commands are invoked instead of NANT.

An Example

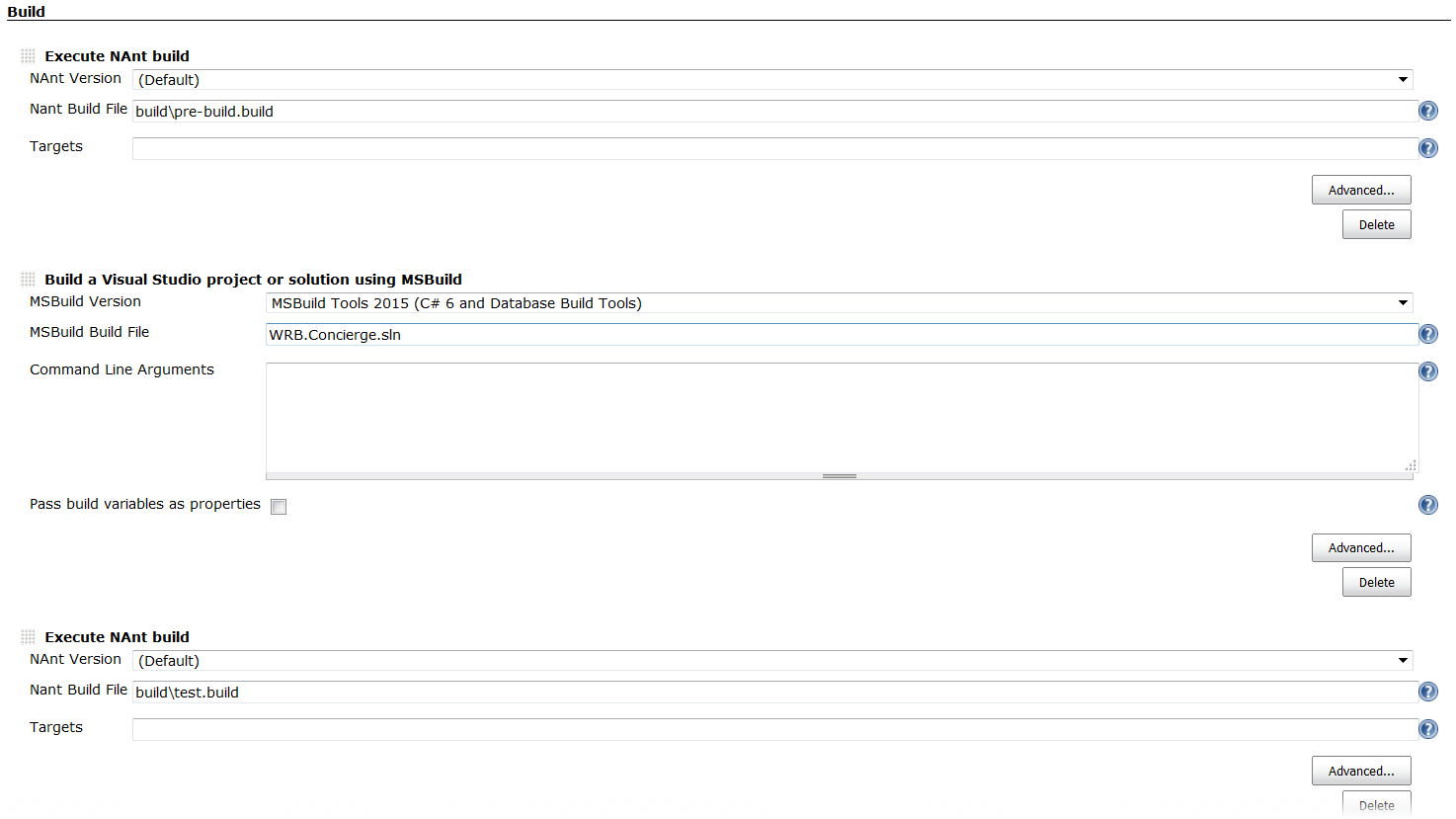

Below is a screen shot from one of my Jenkins jobs. It’s a CI build for a web app and its supporting services. Jenkins handles the source code and compiles the .NET solution (because Jenkins does those two things very well), but otherwise, it invokes the NANT scripts saved in the source repository. These scripts replaced command line steps previously saved in Jenkins.

In this example, pre-build.build runs first and restores dependencies via NuGet. After the source is compiled by MSBuild, test.build runs the tests. There are additional scripts for packaging and deployment not visible in the screen shot. They run after the tests complete successfully.

Below is the pre-build NANT script.

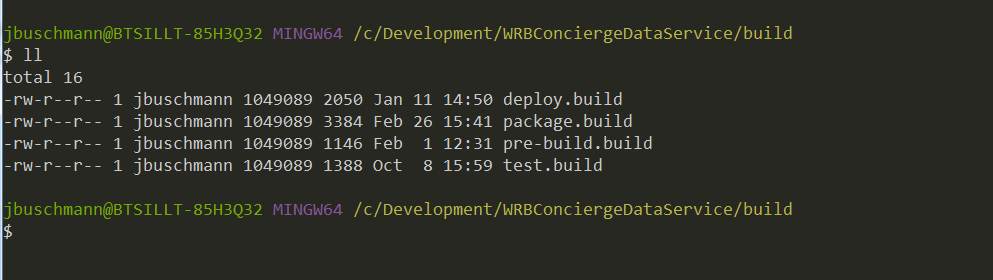

As you can see, developers can modify the build steps without having access to Jenkins. In this case, the project has a Build directory at its root that contains the NANT build scripts. They act as extension points for the build job.

This approach allows for a clear separation of concerns. System administrators handle security and performance on the Jenkins server/cluster, and application developers focus on the specifics of their application’s build process.

Each job is open for extension but closed for modification.

A big thank you to Carolyn Van Slyck whose work inspired this post and who provided valuable feedback. You can find her on Twitter and writing about technology on her blog.